Sanjuro

椿三十郎

"You cut well, but the best sword stays in its sheath!"

Overview

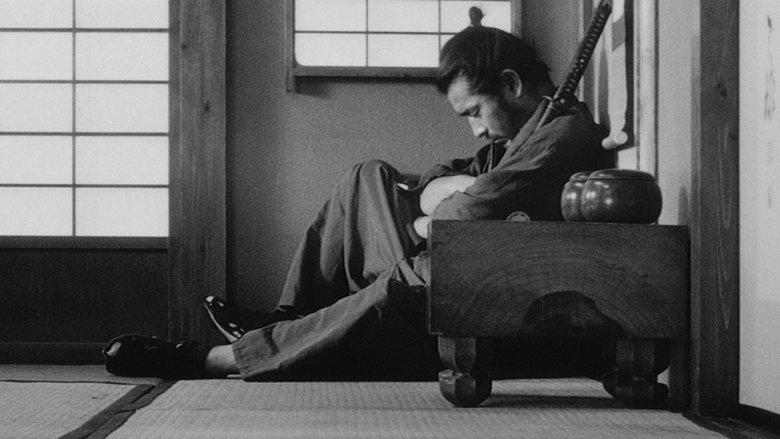

"Sanjuro" (椿三十郎) is Akira Kurosawa's 1962 sequel to his highly successful film "Yojimbo". Toshiro Mifune reprises his role as the masterless samurai, who this time stumbles upon a group of nine idealistic but naive young samurai. Overhearing their clumsy plot to expose corruption within their clan, the ronin realizes they have misidentified the true villain and are walking into a trap set by the superintendent they trust.

Taking pity on their incompetence, the scruffy warrior, who names himself "Tsubaki Sanjuro" (thirty-year-old camellia), decides to help them. What follows is a tense and often humorous series of strategic maneuvers as Sanjuro guides the bumbling youths in their quest to rescue their captured Chamberlain and his family and expose the real conspiracy. The ronin must use his wits and unparalleled sword skills to outsmart the antagonists, led by the cunning and equally formidable samurai Hanbei Muroto (Tatsuya Nakadai).

Core Meaning

The core meaning of "Sanjuro" revolves around a critique of the glorified image of the samurai and the nature of violence. Through the wisdom of the Chamberlain's wife, the film posits that the best sword is one that remains in its sheath. Sanjuro, a master of violence, is forced to confront the idea that killing is a "bad habit" and that true strength lies in restraint and wisdom, not just martial prowess. The film satirizes the rigid, often foolish adherence to the samurai code by the nine young men, contrasting their idealism with Sanjuro's pragmatic and cynical approach. Ultimately, the film suggests that violence is a tragic, ugly necessity, not a source of glory, a lesson Sanjuro tries to impart after the brutal final duel.

Thematic DNA

Appearance vs. Reality

This is a central theme, as the nine young samurai initially judge everyone by their outward appearance. They trust the polished, well-mannered superintendent, who is the true villain, and distrust the scruffy, ill-mannered Sanjuro, who is their only hope. The Chamberlain's wife, a genteel lady, possesses a profound wisdom that challenges Sanjuro's warrior ethos. The film consistently argues that true character and danger cannot be assessed by superficial qualities like dress or social etiquette.

Cynicism vs. Idealism

Sanjuro embodies cynicism born from experience, while the nine young samurai represent untested idealism. Their adherence to protocol and naive assumptions constantly creates problems that Sanjuro's pragmatic, often ruthless, thinking must solve. The film explores the friction between these two worldviews, suggesting that while idealism is noble, it is ineffective and dangerous without the wisdom of experience. Sanjuro's task becomes mentoring these "orphans" in the harsh realities of the world.

The Nature of Violence and True Strength

Unlike its predecessor "Yojimbo," "Sanjuro" overtly questions the morality of killing. The Chamberlain's wife's admonition that Sanjuro is like a "drawn sword" and that "the best sword is kept in its sheath" becomes the film's philosophical core. Sanjuro, who previously killed without remorse, is shown here to avoid bloodshed when possible and regrets it when it's necessary. The shocking violence of the final duel serves not as a glorious climax but as a brutal lesson on the tragic reality of killing, emphasizing that true strength is found in restraint.

Individualism vs. Conformity

The nine young samurai act as a unit, dressing alike and often speaking in unison, representing conformity and adherence to tradition. Sanjuro is their antithesis: a rugged individualist who flouts convention, relies on his own judgment, and thinks independently. The film satirizes the blind loyalty and rigid protocols of the samurai class, championing Sanjuro's unconventional methods as more effective and ultimately more honorable.

Character Analysis

Sanjuro Tsubaki

Toshirō Mifune

Motivation

His initial motivation seems to be a mix of pity for the inept young samurai and perhaps a desire for food and money. However, he is driven by an underlying, albeit deeply buried, sense of justice and responsibility. He feels compelled to help those who cannot help themselves, even as he insults and berates them.

Character Arc

Initially the same cynical, pragmatic ronin from "Yojimbo," Sanjuro undergoes a subtle but significant evolution. Forced into the role of a reluctant mentor, he is repeatedly confronted by the naive idealism of the young samurai and the profound, peaceful wisdom of the Chamberlain's wife. Her critique of him as an "unsheathed sword" forces him to reflect on his violent nature. By the end, after killing his rival Muroto, he doesn't celebrate but expresses anger and regret, demonstrating that he has absorbed the lesson that violence is a tragic flaw, not a virtue.

Hanbei Muroto

Tatsuya Nakadai

Motivation

Muroto is motivated by ambition and a rigid adherence to his own twisted sense of warrior honor. After being publicly and repeatedly fooled by Sanjuro's schemes, his motivation shifts to a personal vendetta, believing that defeating Sanjuro is the only way to reclaim his lost dignity.

Character Arc

Muroto serves as a dark mirror to Sanjuro. He is intelligent, highly skilled, and pragmatic, quickly recognizing Sanjuro's abilities and seeing him as a peer. However, his skills serve a corrupt and selfish cause. His arc is one of escalating frustration and obsession. After being repeatedly outwitted by Sanjuro, his honor is so deeply wounded that he sees killing Sanjuro in a duel as the only way to restore it, leading to his own demise.

Iori Izaka

Yūzō Kayama

Motivation

His primary motivation is a pure, if misguided, desire to root out corruption in his clan and restore honor. He is driven by a strong sense of loyalty to his uncle, the Chamberlain, and a rigid adherence to the samurai code as he understands it.

Character Arc

Izaka is the leader of the nine young samurai. He starts the film with a naive and simplistic view of honor and corruption, leading his group into a trap. Throughout the film, he and his comrades are forced to follow Sanjuro's unconventional and often un-samurai-like methods. His arc is one of learning; he slowly begins to grasp the complexities of the situation and the wisdom behind Sanjuro's abrasive guidance. By the end, he and the others have learned to see beyond appearances, kneeling in respect for their messy, cynical master.

Chamberlain's Wife

Takako Irie

Motivation

Her motivation is to uphold a code of peaceful, civilized conduct, even in the most dangerous of circumstances. She believes in restraint, compassion, and true honor, which she defines not through killing but through wisdom and control. She gently tries to impart this wisdom to Sanjuro.

Character Arc

The Chamberlain's wife is a static but deeply impactful character. She does not change, but instead acts as the catalyst for Sanjuro's change. Despite being a refined, genteel lady seemingly out of place in the violent conflict, she embodies the film's central philosophy. Her polite but firm critiques of violence and her calm wisdom provide the moral compass of the story, challenging the protagonist's worldview and ultimately shaping the film's message.

Symbols & Motifs

The Sheathed vs. The Unsheathed Sword

This is the film's central metaphor for true strength and wisdom. The Chamberlain's wife tells Sanjuro he is like a dangerous "drawn sword." The ideal, she suggests, is the "sheathed sword" – power held in reserve, used only when absolutely necessary. Sanjuro ultimately internalizes this lesson, recognizing his rival Muroto as another unsheathed sword, and sees their duel as a tragedy born of their shared nature.

This is first articulated by the Chamberlain's wife after she is rescued. Sanjuro then repeats this wisdom at the film's conclusion after killing Muroto, telling the young samurai that the lady was right and they should keep their own swords sheathed.

Camellias (Tsubaki)

The camellia flower (Tsubaki) carries multiple meanings. Sanjuro adopts it as part of his name. In Japanese culture, the way camellias drop their entire head at once can symbolize a noble death or, conversely, be seen as unlucky, resembling decapitation. Within the film, they are used practically as a signal. The contrast between the beautiful flowers floating downstream and the bloody violence they are meant to trigger highlights the absurdity of conflict. Kurosawa reportedly wanted the camellias to be the only colored objects in the black-and-white film, but the technology was not ready.

Sanjuro devises a plan to send a large number of camellias down a stream to signal the nine samurai when it is time to attack the compound where the Chamberlain is held. The plan is subverted when his captor, Muroto, becomes suspicious.

Memorable Quotes

The best sword is kept in its sheath.

— Chamberlain's Wife (and later Sanjuro)

Context:

The Chamberlain's wife first says this to Sanjuro, observing that he is like a dangerous "drawn sword." Sanjuro is initially taken aback but internalizes the lesson. He repeats the line to the young samurai at the end of the film after the tragic duel with Muroto, confirming his character's growth.

Meaning:

This quote encapsulates the film's core theme. It argues that true strength and mastery are not demonstrated by constant displays of power and violence, but by restraint and the wisdom to know when *not* to fight. It's a direct critique of the glorification of violence inherent in the samurai mythos.

He was exactly like me. A drawn sword.

— Sanjuro

Context:

Sanjuro says this immediately after killing Muroto in the final duel. He becomes angry when the young samurai cheer his victory, trying to make them understand the grim reality of what just happened.

Meaning:

With this line, Sanjuro acknowledges his rival, Muroto, as his equal and his dark reflection. He sees that they are both defined by their readiness to kill and that this shared nature made their fatal confrontation inevitable. It is a moment of self-realization and regret, where he understands that his 'victory' is also a tragedy and a form of self-destruction.

Killing people is a bad habit.

— Chamberlain's Wife

Context:

The Chamberlain's wife calmly says this to Sanjuro after he has skillfully, and violently, dispatched a number of guards to rescue her and her daughter. Her gentle disapproval has a greater effect on him than any threat.

Meaning:

This simple, almost naive-sounding statement is a profound moral challenge to Sanjuro and the entire samurai genre. It reframes killing not as a glorious or necessary act of a warrior, but as a common, negative behavior that should be controlled. It strips the violence of its mystique and exposes it as a crude habit.

Philosophical Questions

What is the nature of true strength and honor?

The film directly challenges the traditional samurai definition of honor, which is tied to martial prowess and a willingness to die. Through the character of the Chamberlain's wife, it proposes an alternative: true strength lies in restraint, wisdom, and the ability to avoid conflict. The central metaphor of the "sheathed sword" argues that power is most profound when it is controlled. Sanjuro's journey is one of realizing that his skill with a sword is a "bad habit" rather than the pinnacle of his being.

Can a person defined by violence ever truly escape their nature?

"Sanjuro" leaves this question ambiguous. The protagonist learns a profound lesson about the futility and ugliness of killing, yet the film ends with him walking away alone, still a ronin. He rejects the community and stability he helped create, warning the young samurai not to follow him under threat of death. This suggests that while he may have gained wisdom, he is still defined by his violent past and capabilities, unable or unwilling to integrate into the peaceful world he helped restore. He is a tool for restoring order, but not one that can exist within it.

Alternative Interpretations

One alternative reading of the film questions the sincerity of Sanjuro's character development. Some might argue that his adoption of the Chamberlain's wife's philosophy is superficial, and his final departure shows he is incapable of changing his fundamental nature as a violent wanderer. His angry outburst at the end could be seen less as a lesson to the youths and more as self-loathing and frustration with his own inescapable identity as a killer.

Another interpretation focuses on the final duel as a critique of the audience's desire for violence. By building suspense and then delivering a shocking, grotesquely bloody climax, Kurosawa could be seen as confronting the viewer. Sanjuro's subsequent anger at the young samurai for cheering the "brilliant" kill is, by extension, Kurosawa's rebuke to an audience that consumes violence as entertainment, forcing them to acknowledge its ugly reality.

Cultural Impact

"Sanjuro" solidified the archetype of the cynical, scruffy, but brilliant wandering samurai that Toshiro Mifune had established in "Yojimbo." While its predecessor had a more direct influence on Westerns, particularly Sergio Leone's "A Fistful of Dollars," "Sanjuro" was highly influential within the samurai genre itself. Its blend of thrilling action, sharp satire, and social comedy was a departure from more somber samurai tales.

The film's final duel is one of the most iconic and influential scenes in action cinema. The moments of intense stillness followed by a lightning-fast, shockingly brutal conclusion became a staple of the genre. The use of a geyser of blood, whether accidental or not, set a new standard for graphic violence in film and was widely imitated. Critically, the film was a major success in Japan and received acclaim abroad for its clever script, Mifune's powerful performance, and Kurosawa's masterful direction, which balanced humor and serious themes. It is often debated by fans and critics whether it is superior to "Yojimbo," with many praising its lighter tone, more complex character development for Sanjuro, and more polished feel.

Audience Reception

Audiences have generally praised "Sanjuro" as a highly entertaining and worthy sequel to "Yojimbo." Many viewers appreciate its lighter, more humorous tone and find it more accessible than its predecessor. Toshiro Mifune's performance as the gruff, cynical ronin is universally lauded, with many enjoying the comedic elements arising from his exasperation with the naive young samurai.

The action sequences, particularly the iconic final duel, are frequently cited as highlights for their masterful choreography and shocking conclusion. Common points of praise focus on the clever plot, the film's satirical deconstruction of samurai tropes, and its deeper philosophical themes about violence. While some critics and fans consider it a lesser film than the more groundbreaking "Yojimbo," many others prefer "Sanjuro" for its wit, pacing, and the added depth it gives to the main character.

Interesting Facts

- "Sanjuro" was not originally intended as a sequel to "Yojimbo." The script was an adaptation of a Shūgorō Yamamoto novel called "Hibi Heian" (Peaceful Days). Due to the massive success of "Yojimbo," Kurosawa and his screenwriters reworked the story to include the popular ronin character.

- The hero's adopted name changes from "Kuwabatake Sanjuro" (mulberry field) in "Yojimbo" to "Tsubaki Sanjuro" (camellia) in this film. In both cases, he names himself after the nearest plant life when asked for a name.

- The iconic final duel, which ends with a massive, high-pressure spray of blood, was reportedly an intentional effect by Kurosawa, though some stories claim it was an accident. The "blood" was a mixture of chocolate syrup and carbonated water, and the pump malfunctioned, releasing a much larger torrent than planned. Kurosawa loved the result and kept it.

- "Sanjuro" was the only sequel Akira Kurosawa ever directed, aside from the studio-mandated "Sanshiro Sugata Part Two."

- While "Yojimbo" was heavily influenced by the American Western genre, "Sanjuro" is considered a more traditional Japanese 'jidaigeki' (period drama), focusing on a clan's internal power struggle.

- "Sanjuro" was Toho's highest-grossing film of 1962, earning ¥450.1 million in distributor rentals.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!