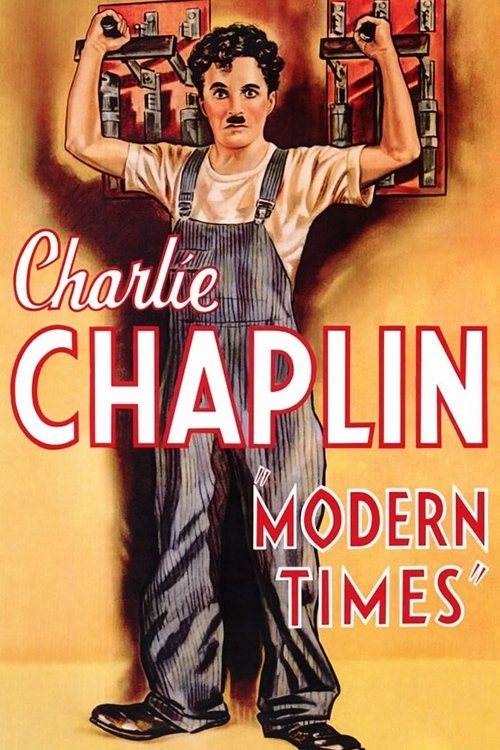

Modern Times

"He stands alone as the greatest entertainer of modern times! No one on earth can make you laugh as heartily or touch your heart as deeply...the whole world laughs, cries and thrills to his priceless genius!"

Overview

"Modern Times" marks Charlie Chaplin's final performance as his iconic Little Tramp character. The film finds the Tramp as a factory worker struggling to survive in the modern, industrialized world. Pushed to his limits by the monotonous, high-speed assembly line, he suffers a nervous breakdown, leading to a series of comedic misadventures.

After being hospitalized, he is released into a world grappling with the Great Depression, marked by unemployment and social unrest. He soon crosses paths with a spirited, orphaned young woman, known as the Gamin (Paulette Goddard), who is also fighting to survive on the streets. Together, they form a bond and dream of a simple, happy life, navigating a series of jobs—from a night watchman to a singing waiter—and constant run-ins with the law in their quest for a place in a society that seems to have no room for them.

Core Meaning

"Modern Times" is a powerful critique of the dehumanizing effects of industrialization and the societal struggles during the Great Depression. Chaplin uses the Tramp's journey to explore the conflict between humanity and the machine, arguing that an obsessive focus on efficiency and profit strips individuals of their autonomy and spirit. The film posits that in a mechanized, profit-driven world, institutions like factories and even prisons operate on a similar logic of control, turning people into mere cogs. Ultimately, the core message is one of resilience; despite the overwhelming forces of an indifferent society, the human spirit's capacity for hope, companionship, and the dream of a better life can endure.

Thematic DNA

Dehumanization and Industrialization

The film's central theme is the critique of modern industry's impact on the individual. This is vividly portrayed in the opening factory sequences, where workers are equated to a flock of sheep and The Tramp is literally consumed by the gears of a giant machine. The relentless pace of the assembly line leads to his nervous breakdown, showing how monotonous, repetitive labor can crush the human spirit. The invention of a "feeding machine" to eliminate lunch breaks further satirizes the obsession with efficiency at the expense of human dignity.

Poverty, Unemployment, and the Great Depression

Set against the backdrop of the Great Depression, the film directly confronts the realities of widespread unemployment, hunger, and social inequality. Characters like the Gamin and "Big Bill" are driven to steal not out of malice, but out of desperation and hunger. The Tramp's repeated preference for the security of jail over the hardships of the streets serves as a biting commentary on the lack of a social safety net, suggesting that prison provides more stability than a life of freedom in a struggling economy.

Hope and Resilience

Despite the bleak social landscape, the film is imbued with a powerful sense of optimism. The relationship between The Tramp and the Gamin is the heart of this theme. They face constant setbacks—losing jobs, their home, and being pursued by authorities—yet they never give up. The final, iconic shot of them walking hand-in-hand down an open road towards the horizon symbolizes their unbreakable spirit and the belief that, together, they can face an uncertain future with hope.

Critique of Capitalism and Authority

The film satirizes the structures of power within a capitalist society. Factory owners are depicted as detached and authoritarian, monitoring workers via large screens and caring only for productivity. The police are often portrayed as instruments of oppression, breaking up strikes and relentlessly pursuing the poor for minor infractions while ignoring the systemic causes of their plight. The Tramp's accidental leadership of a communist protest, simply by picking up a red flag, mocks the paranoia of the era and the tendency of authorities to misunderstand and persecute the working class.

Character Analysis

A Factory Worker (The Tramp)

Charlie Chaplin

Motivation

Initially, his motivation is simple survival and, at times, a comical desire to return to the relative comfort of prison. After meeting the Gamin, his motivation shifts to building a life and a home with her, embodying the universal dream for happiness and domesticity, however humble.

Character Arc

The Tramp begins as a cog in the industrial machine, literally broken by his work. His journey is a cyclical struggle of trying to fit into various roles society offers—factory worker, prisoner, night watchman, waiter—and failing comically at each. He finds purpose not in conforming, but in his relationship with the Gamin. His arc is not about achieving societal success but about discovering that resilience and happiness come from human connection, ending his journey not alone, but with a companion to face the future.

A Gamin

Paulette Goddard

Motivation

Her primary motivation is survival and escaping the clutches of the juvenile welfare officers who threaten her freedom. This broadens to a desire for stability, love, and a home, a dream she shares with The Tramp and actively works towards by securing them both jobs.

Character Arc

The Gamin starts as a fiercely independent orphan, stealing to feed her family and fleeing authorities. After meeting The Tramp, she channels her resourcefulness into their shared dream of a home. She is the catalyst for The Tramp's more concerted efforts to find work and is often the more pragmatic of the two. While she has moments of despair, her spirit is rekindled by The Tramp's optimism, and she evolves from a lone survivor into a hopeful partner.

Big Bill

Tiny Sandford

Motivation

His motivation is simple and stark: hunger. As he tells The Tramp during the robbery, "We ain't burglars, we're hungry." This line encapsulates the plight of the unemployed during the Great Depression.

Character Arc

Big Bill is first seen as a fellow assembly line worker alongside The Tramp. He later reappears as a burglar in the department store where The Tramp is a night watchman. His arc demonstrates the social decay caused by unemployment; a once-honest worker is forced into crime by hunger and desperation. His recognition of The Tramp humanizes him, showing that his actions stem from need, not malice.

Café Proprietor

Henry Bergman

Motivation

His motivation is to run a successful café. He is willing to take a chance on new talent, first with the Gamin and then, reluctantly, with The Tramp, recognizing their potential to entertain his customers.

Character Arc

The Café Proprietor represents a rare opportunity for legitimate success for the main characters. He initially sees potential in the Gamin's dancing and hires her. Despite The Tramp's disastrous performance as a waiter, the proprietor gives him a second chance as a singer, which proves to be a huge success. His arc, though brief, provides a glimpse of the stability the couple yearns for before it is snatched away by outside forces.

Symbols & Motifs

The Factory Machine

The giant machine symbolizes the overwhelming and dehumanizing power of modern industry. It represents a system that consumes the individual, turning human beings into mindless automatons or literal cogs in its operation, prioritizing production over well-being.

The most iconic scene of the film features The Tramp being swallowed by the gears of the massive assembly line machine. His body is pulled through its inner workings, a visual metaphor for his loss of control and identity within the industrial system.

Sheep

The film opens by cross-cutting between a flock of sheep and a crowd of workers leaving a subway. This allegory suggests that workers in industrial society are like herded animals: docile, undifferentiated, and led blindly to their daily grind, sacrificing their individuality for the sake of the system.

This symbolic comparison is the very first visual statement of the film, immediately following the title cards, establishing the central theme of dehumanization before any characters are introduced.

The Clock

The large clock shown in the opening credits symbolizes the tyranny of time in the industrial age and the obsession with efficiency. It represents the regimented, controlled nature of modern life, where human activity is dictated by the relentless, mechanical pace of the factory rather than natural rhythms.

The film's credits are superimposed over a giant clock face, its hands moving steadily forward, setting the stage for the pressure and pace that will drive The Tramp to his breaking point.

The Open Road

The road represents freedom, hope, and the possibility of a future that lies beyond the confines of oppressive societal structures. It is a space where The Tramp and the Gamin, as outsiders, can forge their own path together, even if the destination is unknown.

The final, iconic shot of the film shows The Tramp and the Gamin walking hand-in-arm down a long, empty road towards the dawn. After facing despair, The Tramp encourages her to smile, and they continue their journey with renewed hope.

Memorable Quotes

(Nonsense Song Lyrics) Se bella giu satore je notre so cafore, je notre si cavore je la tu la ti la twah...

— A Factory Worker (The Tramp)

Context:

Working as a singing waiter, The Tramp loses the cuffs on which he'd written the lyrics to his song. Urged on by the Gamin, he improvises the song with nonsensical words and expressive pantomime, winning over the audience with his charismatic performance.

Meaning:

This is the first and only time audiences hear The Tramp's voice. By singing in gibberish—a mix of fake French and Italian—Chaplin cleverly preserved the character's universal appeal, which he feared would be lost if the Tramp spoke a specific language. The song's success in the film demonstrates that emotion and story can be conveyed through performance and intonation alone, transcending language barriers.

Buck up - never say die. We'll get along!

— A Factory Worker (The Tramp)

Context:

In the final scene, the Gamin is heartbroken after they are forced to flee their jobs at the café. Sitting by the side of the road, she asks, "What's the use of trying?" The Tramp delivers this line, lifts her spirits, and they walk off down the road together.

Meaning:

This intertitle quote encapsulates the film's core message of hope and resilience. After facing their latest and most crushing defeat, The Tramp refuses to give in to despair. His words are a simple yet profound affirmation of their ability to survive and find happiness together, no matter the obstacles.

We ain't burglars. We're hungry.

— Big Bill

Context:

The Tramp, working as a night watchman in a department store, confronts a trio of armed burglars. He recognizes one of them, "Big Bill," as his former co-worker from the factory. Big Bill says this line to explain their actions, transforming a dangerous encounter into a moment of shared struggle.

Meaning:

This line provides a powerful social commentary on the connection between poverty and crime during the Great Depression. It reframes the burglars not as villains, but as desperate, unemployed factory workers driven to theft by starvation. It highlights one of the film's key themes: that societal and economic systems, not individual moral failings, are often the root cause of crime.

Philosophical Questions

What is the relationship between humanity and technology, and at what point does efficiency begin to erode humanity?

The film explores this question through the factory scenes. The assembly line is designed for maximum efficiency, but it pushes The Tramp to a mental breakdown. The "feeding machine" is the ultimate parody of this idea, a technological solution that ignores the human need for rest and dignity. Chaplin suggests that when technology is used solely for profit without regard for human well-being, it becomes an oppressive force that turns people into extensions of the machines they operate.

In an unjust society, what is the true meaning of freedom and confinement?

"Modern Times" subverts the conventional understanding of freedom. The Tramp finds life in prison to be more comfortable and secure than his life as a free but unemployed man on the streets. He actively tries to get arrested to escape the chaos and hunger of the outside world. This ironic preference suggests that in a society that fails to provide basic necessities, the regimented security of confinement can feel more liberating than a "freedom" that amounts to a constant, desperate struggle for survival.

Can hope and individualism survive in the face of overwhelming systemic oppression?

The entire narrative of the film is a testament to this question. The Tramp and the Gamin are relentlessly beaten down by the economic and social systems of their time. They lose jobs, their home, and are constantly pursued by the law. Yet, the film's answer is a resounding 'yes'. Their survival is rooted in their companionship and their persistent, almost irrational optimism. The final scene argues that the will to "buck up" and keep trying is the ultimate act of defiance against a dehumanizing world.

Alternative Interpretations

While the ending of "Modern Times" is widely seen as optimistic, some interpretations view it with a degree of ambiguity. The hopeful shot of The Tramp and the Gamin walking toward the horizon can be read not as a guarantee of future success, but as the beginning of another cycle of struggle. They are, after all, still homeless, unemployed, and on the run. This reading suggests that their hope is a necessary illusion for survival in a system that will continue to thwart them. Their personal bond is a triumph, but it exists in defiance of a society that has not changed.

Another area of debate concerns the film's political stance. While often read as a critique of capitalism, Chaplin himself was careful to distance the film from overt communist propaganda. The scene where The Tramp accidentally leads a communist protest is played for laughs, which can be interpreted as Chaplin satirizing both the authorities' paranoia and the communists themselves. Some critics argue the film is not a specific political tract but a broader, humanist plea for the individual against any form of oppressive, dehumanizing system, whether capitalist or otherwise.

A darker interpretation suggests that the various institutions The Tramp experiences—the factory, the hospital, the prison—are not distinct entities but different faces of the same monolithic, controlling society. In this view, his "freedom" outside these institutions is just a more chaotic version of confinement, and his desire to return to jail is a rational choice for stability in an irrational world, making the film a bleaker commentary on the illusion of freedom in modern society.

Cultural Impact

Released in 1936, "Modern Times" served as a poignant and timely commentary on the Great Depression and the anxieties surrounding industrialization. It was one of the few mainstream films of its time to directly address issues like unemployment, poverty, and labor strikes. The film's critique of assembly-line labor and the dehumanizing pursuit of efficiency was seen by some as having leftist or communist sympathies, a perception that would contribute to Chaplin's later political troubles in the U.S. Despite this, the film was a major box office success and was hailed by many critics as a masterpiece.

Its influence on cinema is immense. The iconic image of The Tramp caught in the gears of a machine has become a universal symbol for the struggle between humanity and technology. The film's blend of slapstick comedy with sharp social satire set a high bar for political filmmaking. French philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir even named their influential journal, Les Temps Modernes, after the film. In 1989, it was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant." The film's themes remain remarkably relevant, resonating in contemporary discussions about automation, labor rights, and economic inequality.

Audience Reception

Upon its release, "Modern Times" was a critical and commercial success, and it is now considered one of Chaplin's greatest films. It currently holds a 98% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes and a score of 96 out of 100 on Metacritic, indicating "universal acclaim." Audiences and critics praised its hilarious slapstick comedy, particularly the iconic factory sequences and the singing waiter scene. Many also lauded its poignant social commentary on the hardships of the Great Depression, seeing it as a brave and timely statement. However, the film's political undertones were a point of contention. Some conservative reviewers downplayed or ignored its social critique, while left-wing critics hailed it as a powerful anti-capitalist statement. The film's perceived leftist sympathies drew criticism in some quarters and were later used against Chaplin during the McCarthy era. Despite the political debates, the film's blend of humor and pathos resonated deeply with audiences, and its enduring message of hope in the face of adversity remains a key reason for its beloved status.

Interesting Facts

- "Modern Times" was the last film to feature Charlie Chaplin's iconic Little Tramp character.

- Although released well into the sound era, the film is mostly silent, using synchronized music and sound effects. Chaplin resisted dialogue because he believed the Tramp's universal appeal would be lost if he spoke.

- The famous "Nonsense Song" marks the first time Chaplin's own voice was heard on film. The lyrics are deliberate gibberish, a mix of faux-French and Italian, to maintain the Tramp's universality.

- A full dialogue script was initially written, and Chaplin even filmed some scenes with dialogue before abandoning the idea and reverting to a primarily silent format.

- The film's romantic theme music, composed by Chaplin himself, was later given lyrics and became the classic pop standard "Smile," famously recorded by Nat King Cole.

- An alternate, sadder ending was filmed where the Gamin becomes a nun and The Tramp is left alone after being released from a hospital. Chaplin opted for the more hopeful ending of them walking down the road together.

- Chaplin was inspired by stories of factory workers suffering nervous breakdowns on the assembly lines of Henry Ford's auto plants. He also discussed the negative impact of profit-driven technology with Mahatma Gandhi, which influenced the film's themes.

- The voices of authority figures, such as the factory president, are only ever heard through mechanical devices like video screens or radios, reinforcing the theme of technology's dehumanizing role.

- The harrowing roller-skating scene, where The Tramp appears to skate dangerously close to a ledge, was achieved using a clever visual effect involving a matte painting. Chaplin was never in any actual danger.

Easter Eggs

In the opening montage comparing workers to sheep, a single black sheep can be seen briefly in the flock.

This is a subtle visual metaphor for The Tramp himself. The black sheep is an individual who stands out from the herd, an outsider who doesn't conform. This quick shot foreshadows The Tramp's inability to fit into the regimented, conformist world of modern industrial society.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!