8½

"A picture that goes beyond what men think about - because no man ever thought about it in quite this way!"

Overview

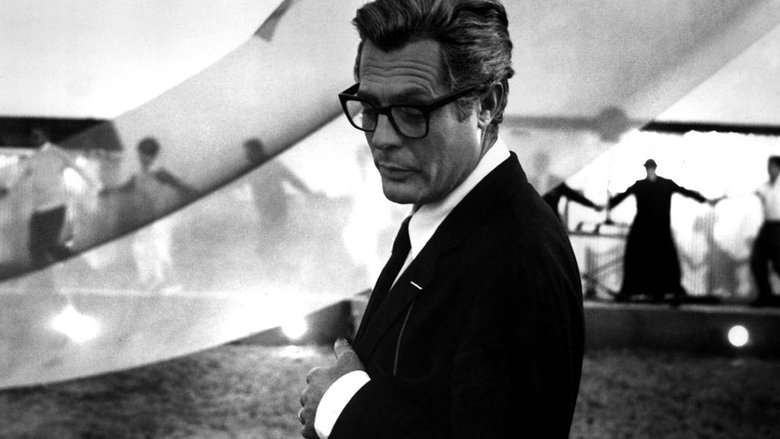

"8½" follows Guido Anselmi, a famous Italian film director who has lost his inspiration. He is supposed to be shooting his next big film, a sprawling science-fiction epic, but he has no script and no clear idea of what the movie is even about. To escape the immense pressure from his producer, crew, and actors, he retreats to a luxurious spa, hoping to find a cure for his creative block and physical exhaustion.

Instead of finding clarity, Guido becomes increasingly lost in a whirlwind of his own memories, dreams, and surreal fantasies. The film fluidly shifts between his present reality at the spa and these vivid, often bizarre, excursions into his subconscious. These inner visions include formative childhood memories, his complex relationships with various women, and fantastical scenarios like a harem where all the women in his life cater to him. His troubled marriage to his estranged wife, Luisa, and his affair with his mistress, Carla, further complicate his personal and professional crisis.

As the production start date looms, Guido's anxieties mount. He is haunted by the expectations of others and his own inability to create something honest and meaningful. The film he is trying to make becomes a mirror of his own confused life, a chaotic spectacle he can no longer control, leading him toward a profound personal and artistic crossroads.

Core Meaning

At its core, "8½" is a profound exploration of the creative process and the struggle for artistic and personal authenticity. Director Federico Fellini uses the protagonist, Guido, as a stand-in for himself, turning his own creative block following the success of La Dolce Vita into the central subject of the film. The film argues that art and life are inextricably linked; Guido's inability to make his film stems from his inability to make sense of his own life, his relationships, and his past.

The message of the film is one of acceptance. Guido's breakthrough does not come from finding a perfect, coherent idea for his movie, but from embracing the chaos, the contradictions, the memories, and the flaws of his life. The celebrated final sequence, where all the characters from his life join hands in a circus-like procession, symbolizes this ultimate acceptance. Fellini suggests that true creation is not about imposing order on life, but about finding the courage to honestly portray its beautiful, messy, and fragmented nature. It is a celebration of the artist's inner world and the idea that our anxieties and imperfections are not obstacles to creativity, but its very source.

Thematic DNA

The Crisis of Creativity

This is the central theme, embodied by Guido's severe "director's block." He is a celebrated filmmaker hounded by producers, actors, and critics to create his next masterpiece, yet he has nothing coherent to say. This struggle is portrayed as an internal, existential crisis. The film suggests that artistic creation is not a simple act of will but a deeply personal and often painful excavation of the self, where the artist must confront their own lies, fears, and inadequacies. Guido's block is a direct result of his personal disarray and his fear of being dishonest in his work.

The Blurring of Reality and Fantasy

"8½" is famous for its seamless transitions between Guido's objective reality and his subjective inner world of dreams, memories, and fantasies. The film does not always provide clear markers for these shifts, immersing the viewer directly into Guido's consciousness. This technique illustrates how memory and imagination are not separate from life but actively shape one's perception of it. Fantasies, like the harem sequence, reveal his desires and guilt, while childhood memories explain his present-day anxieties and relationships with women. This fusion creates the film's signature dreamlike quality and reinforces the idea that life is a subjective experience.

Memory and Childhood

Guido is constantly retreating into his past, particularly his Catholic upbringing and his first sexual awakenings. Key flashbacks, like his encounter with the prostitute Saraghina on the beach and his subsequent punishment by priests, are shown to be formative experiences that have shaped his adult psyche, his guilt, and his complicated views on women and religion. These memories are not just nostalgic interludes but active forces in his present, haunting him and demanding to be understood before he can move forward as a person and an artist.

Male Infidelity and Relationships with Women

Guido's life is defined by his relationships with a multitude of women who represent different facets of his desires and anxieties. There is his intelligent but long-suffering wife Luisa, his sensual and demanding mistress Carla, and the idealized, angelic actress Claudia. His inability to love or commit to any of them honestly is a primary source of his personal chaos and creative impotence. The film explores themes of male chauvinism, particularly in the famous harem fantasy, but also critiques Guido's inability to see women as whole individuals rather than projections of his needs.

Character Analysis

Guido Anselmi

Marcello Mastroianni

Motivation

Guido's primary motivation is to find something honest and true to say through his art. He is tormented by the feeling that he is a fraud and a liar, and he desperately wants to create a film that is pure and meaningful. On a personal level, he seeks salvation and peace, hoping that an idealized woman or a successful film can rescue him from his confusion, guilt, and marital problems.

Character Arc

Guido begins the film in a state of paralysis, creatively and emotionally blocked, and dishonest with himself and everyone around him. He escapes into fantasies and memories rather than confronting his problems. His journey is entirely internal. After a series of humiliating failures, including a disastrous press conference and a fantasy of his own suicide, he hits rock bottom. This breakdown leads to a breakthrough: he abandons his pretentious film and accepts the chaotic truth of his life. His arc is a move from creative sterility and self-deception to a joyful acceptance of imperfection, culminating in his decision to make a film about his own confusion.

Luisa Anselmi

Anouk Aimée

Motivation

Luisa is motivated by a desire for honesty and genuine connection with her husband. She is fed up with his lies and his self-absorbed artistic temperament. She represents a call to reality and emotional truth that Guido spends most of the film trying to avoid. Her motivation is to be seen and respected as a person, not just another character in his psychodrama.

Character Arc

Luisa is Guido's intelligent and elegant wife, who is painfully aware of his infidelities and the way he uses their life as material for his films. Initially, she is hurt and resentful, maintaining a dignified but cold distance. Her arc is subtle; she doesn't change so much as she is given the space to voice her pain. In the end, Guido asks for her acceptance, and while her expression remains pained, she joins the final procession, suggesting a fragile hope for reconciliation based on his newfound, albeit difficult, honesty.

Carla

Sandra Milo

Motivation

Carla is motivated by a desire for Guido's affection and attention. She enjoys the lifestyle he provides and seems to genuinely care for him, even if their relationship is superficial. She wants to be a more central part of his life, a desire that Guido is unwilling and unable to fulfill.

Character Arc

Carla is Guido's flamboyant and sensual mistress. She is a source of earthly pleasure for Guido but also another complication he cannot manage. She does not have a significant arc; rather, she remains a consistent presence representing a kind of gaudy, uncomplicated sensuality that both attracts and repels Guido. He tries to hide her away, but she continually intrudes on his life, highlighting his inability to keep the different parts of his life separate.

Claudia

Claudia Cardinale

Motivation

In Guido's fantasy, her motivation is simply to save him. As a real person, her motivation is that of a professional actress trying to understand her role. More symbolically, her motivation is to speak the truth, acting as a clear-eyed mirror reflecting Guido's own failings back at him.

Character Arc

Claudia exists for most of the film as a fantasy figure for Guido—an angelic, pure woman in white who he believes will be the key to his film and his salvation. Her arc is the shattering of this ideal. When Guido finally meets the real actress, she is a real person, not the symbol he imagined. In a crucial scene, she becomes his confessor, telling him bluntly that his problem is that he "doesn't know how to love." She rejects the idealized role he has created for her, forcing him to confront his own lies.

Symbols & Motifs

The Spa / Water

Water in the film symbolizes purity, healing, and salvation, but its meaning is complicated. The spa offers "holy water" as a cure for all ailments, reflecting Guido's search for a simple solution to his complex problems. However, this same water makes his mistress sick, suggesting that easy cures are illusory. The sea, where the prostitute Saraghina lives, also represents a more primal, perhaps purer, form of life, contrasting with the repressive doctrines of the church.

The film is set at a spa where Guido is "taking the cure." He is prescribed to drink the mineral water, and the setting is filled with imagery of baths and springs. He also describes his ideal woman, Claudia, as a healing figure who gives him water from a spring.

The Spaceship / Tower of Babel

The massive, unfinished spaceship set for Guido's film is a powerful symbol of his artistic hubris and creative impotence. It is often compared to the Tower of Babel, a monument to human arrogance that was ultimately left unfinished. The structure represents the grandiose, meaningless project Guido feels pressured to create. Its eventual dismantling signifies the collapse of his false artistic ambitions and the beginning of a more honest approach to his work.

The gigantic steel structure looms over many scenes at the beach location for Guido's film. It is the central set piece for the movie-within-the-movie. At the climax, a disastrous press conference is held at its base, and Guido finally orders it to be torn down.

The Circus / Parade

The circus motif represents life itself—a chaotic, beautiful, and collaborative performance. For Fellini, the circus was a recurring image of magic, community, and the suspension of disbelief. In "8½", it symbolizes Guido's ultimate realization that he must embrace all the characters and experiences of his life, orchestrating them into a harmonious whole, much like a ringmaster.

The film's final, iconic scene takes the form of a circus parade. A magician, acting as a ringmaster, calls all the figures from Guido's life—real and imagined—to join hands and march in a circle around the spaceship set, led by a troupe of clowns and a band. Guido joins them, accepting his role as the director of his own life's circus.

White and Black Clothing

The film's black-and-white cinematography is used symbolically. White often represents Guido's idealized, pure vision of women, particularly the ethereal Claudia who appears in his fantasies dressed in all white. Black can symbolize the corruption of this ideal or the complexities of reality. When Guido meets the real Claudia, she is dressed in black, shattering his fantasy. Guido himself often wears a black suit with a white shirt, visually representing his internal conflict between purity and corruption, artifice and authenticity.

Throughout the film, characters' costumes are starkly black or white. Claudia's appearances in Guido's dreams and fantasies feature her in flowing white gowns. The prostitute Saraghina also wears a white scarf. In contrast, the real-world Claudia and many of the film industry figures wear black.

Memorable Quotes

I wanted to make an honest film. No lies whatsoever. I thought I had something so simple to say... Instead, it's me who lacks the courage to bury anything at all.

— Guido Anselmi

Context:

Guido confesses this to Rossella, his wife's best friend, while they are at the massive spaceship set. He is expressing his deep confusion and despair over the state of his film and his life, admitting that the project has become a monstrous testament to his own lack of courage.

Meaning:

This quote encapsulates the central crisis of the film. It is Guido's confession of his artistic and moral failure. He began with a noble intention—to create something pure and true—but realizes that he himself is the source of the dishonesty, unable to confront the "dead things" within himself. It highlights the immense difficulty of achieving true authenticity in art and life.

Because he doesn't know how to love.

— Claudia

Context:

This exchange occurs when Guido finally meets with the real Claudia to explain her role in his film. He describes a protagonist (himself) who is saved by a pure woman but ultimately pushes her away. When he tries to explain the character's motivations, Claudia repeatedly interrupts with this simple, devastating truth.

Meaning:

This line, repeated three times, is the film's bluntest and most accurate diagnosis of Guido's problem. Claudia, the object of his idealized fantasies, becomes the voice of truth, cutting through all of his artistic and existential excuses. She clarifies that his creative block isn't about a lack of ideas but a fundamental emotional and moral failing. His inability to love authentically is the root of his inability to create authentically.

What is this sudden happiness that makes me tremble, giving me strength, life? ... I hadn't understood. I didn't know. It's so natural accepting you, loving you. And so simple.

— Guido Anselmi (internal monologue)

Context:

This is Guido's internal thought process during the final scene, just before the circus parade begins. He has just ordered the spaceship set to be dismantled and has listened to his critic Daumier praise him for abandoning the project. But a magician prompts a change of heart, and as Guido looks at his wife, he has this profound realization.

Meaning:

This marks Guido's epiphany and the film's emotional climax. After hitting rock bottom and giving up on his film, he suddenly realizes that the answer is not to reject the chaos of his life but to embrace it. The happiness he feels comes from acceptance—of himself, his flaws, and all the people in his life. It is the moment he stops fighting and finds freedom in surrender, which allows him to finally create.

Life is a party. Let's live it together.

— Guido Anselmi

Context:

This line is spoken by Guido through a megaphone near the very end of the film, as he directs the celebratory parade of all the characters from his life. He is now the confident ringmaster, orchestrating the beautiful chaos he has finally embraced.

Meaning:

This is the ultimate resolution of Guido's crisis. It's a simple, joyful affirmation of life in all its complexity. The metaphor of a party or a festival suggests celebration, community, and participation rather than isolated suffering. It's his invitation to his wife, and to the audience, to join him in this new, accepting vision of life and art.

Philosophical Questions

What is the relationship between art and life?

"8½" posits that art and life are not separate but are deeply intertwined, with one constantly feeding and reflecting the other. Guido's creative block is a direct symptom of his personal life being in disarray—his lies, his troubled marriage, his unresolved childhood traumas. He cannot create an honest film because he is not living an honest life. The film argues that true artistic expression requires a profound and courageous engagement with one's own experiences, flaws, and contradictions. The only way Guido can make his film is to make it about his failure to make a film, thereby turning his life's chaos directly into his art's subject matter.

Can one achieve authenticity in a world of artifice?

Guido is obsessed with the idea of making an "honest film" with "no lies whatsoever," yet he is a compulsive liar in his personal life and works in the medium of cinema, which is inherently an artifice. The film explores this paradox by suggesting that authenticity is not about achieving some objective, unblemished truth. Instead, it is found in the honest admission of one's own confusion and fragmentation. Guido finds his authentic voice not by discovering a simple, pure message, but by embracing the messy, contradictory, and multifaceted nature of his own consciousness and presenting it truthfully.

How do memory and fantasy shape our reality?

The film's structure, which fluidly moves between the present, memory, and fantasy, suggests that our reality is not a fixed, objective state. It is constantly being shaped and interpreted through the lens of our past experiences and our inner desires. Guido's memories of his Catholic upbringing inform his adult guilt, while his fantasies of an ideal woman prevent him from engaging with the real women in his life. Fellini demonstrates that the subconscious is not a hidden realm but an active force that colors every moment of our waking lives, making the line between the internal and external world porous and indistinct.

Alternative Interpretations

While the dominant interpretation of "8½" sees the ending as a triumphant moment of self-acceptance for Guido, some alternative readings offer a more ambiguous or even cynical perspective. One interpretation suggests that the final circus parade is not a breakthrough into reality but just another one of Guido's elaborate fantasies—perhaps his most grandiose one yet. In this view, he has not truly resolved his issues but has simply chosen to escape into a beautifully orchestrated illusion, reinforcing his tendency to prioritize artifice over genuine human connection. His plea to Luisa is just another line in his script.

Another perspective focuses on the film as a critique of male solipsism. From this viewpoint, Guido's final "acceptance" is profoundly selfish. He asks everyone in his life, particularly his long-suffering wife, to accept him exactly as he is, flaws and all, without any promise of change. The celebratory ending can thus be seen as a validation of the narcissistic artist who successfully incorporates everyone into his personal vision, rather than a genuine moment of mutual understanding and reconciliation. The film, then, becomes a darkly ironic portrait of the male ego's ability to reframe its failings as a form of profound artistic truth.

Cultural Impact

"8½" is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential films ever made. Upon its release in 1963, it was met with near-universal acclaim for its innovative, self-reflexive narrative and its masterful blend of fantasy and reality. It firmly established Federico Fellini as a leading figure of international art-house cinema. The film's subject—a film about the making of a film—was a landmark in modernist, self-referential art. It broke conventional narrative rules by prioritizing the psychological state of its protagonist, creating a "stream of consciousness" style that had rarely been seen in cinema.

Its influence on subsequent generations of filmmakers is immense and undeniable. Directors like Martin Scorsese, Woody Allen, David Lynch, and Terry Gilliam have all cited "8½" as a major inspiration. Its exploration of a director's creative and personal crisis has become a recurring subgenre, with films like Bob Fosse's "All That Jazz" and Woody Allen's "Stardust Memories" being direct homages. The film's visual language—its fluid camera movements, striking black-and-white cinematography, and carnivalesque imagery—has been emulated in countless films, music videos, and fashion shoots. "8½" changed the language of cinema, proving that a film's subject could be the struggle of its own creation and that a narrative could be driven by the internal logic of dreams and memory. It remains a timeless meditation on art, identity, and the search for meaning in a fragmented modern world.

Audience Reception

Upon its release, "8½" was met with widespread critical acclaim both in Italy and internationally. Critics praised its audacious and innovative narrative structure, its stunning visual style, and its profound, personal exploration of an artist's inner turmoil. It was seen as a groundbreaking work of modernist cinema. The film was also a commercial success, resonating with audiences who were captivated by its dreamlike quality and its complex, relatable protagonist. It won numerous awards, including the Grand Prize at the Moscow International Film Festival and two Academy Awards. While a minority of critics at the time dismissed it as self-indulgent or confusing, the overwhelming consensus was that it was a masterpiece. Over the decades, its reputation has only grown, and it consistently ranks among the greatest films ever made in polls of critics and directors worldwide.

Interesting Facts

- The title "8½" refers to the number of films Federico Fellini had directed up to that point: six full features, two short films (counting as one), and a co-directed film, which he counted as half a film.

- Fellini himself was suffering from a creative block after his film "La Dolce Vita," and the entire premise of "8½" was born from his own anxiety and uncertainty about what his next film should be.

- Marcello Mastroianni, who plays Guido, reportedly modeled many of his mannerisms, gestures, and even his way of speaking directly on Fellini, making the character a true alter ego.

- The script was often a work in progress, with Fellini frequently rewriting scenes on the day of shooting. The cast was often not told what the film was about, adding to the chaotic and spontaneous atmosphere of the production.

- The film won two Academy Awards: Best Foreign Language Film and Best Costume Design (for Black-and-White).

- The influential final scene, with all the characters joining in a circus-like parade, was an idea Fellini came up with very late in the production process.

- The film's score was composed by Nino Rota, a frequent collaborator of Fellini's, whose music is essential to the film's blend of melancholic and carnivalesque tones.

- Woody Allen has cited "8½" as a major influence, and his film "Stardust Memories" (1980) is a direct homage to it.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!