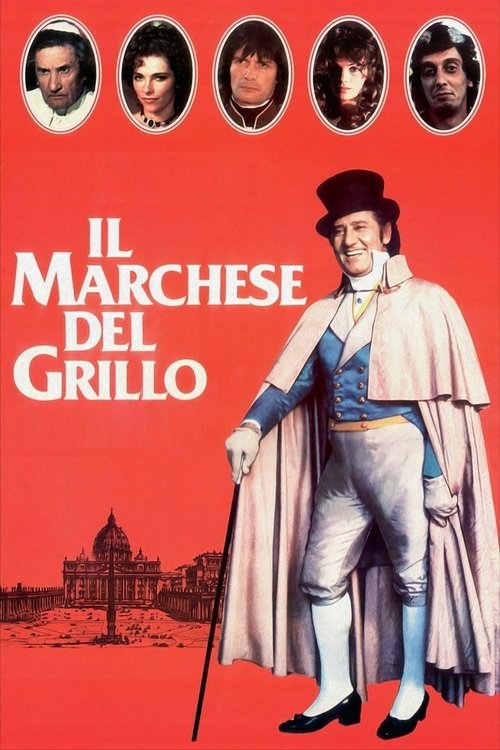

The Marquis of Grillo

Il marchese del Grillo

Overview

Set in Rome in 1809, during the Napoleonic occupation, "The Marquis of Grillo" follows the life of Onofrio del Grillo, a wealthy, cynical, and hedonistic nobleman at the papal court. To escape the boredom of his aristocratic existence, the Marquis dedicates his time to elaborate and often cruel pranks played on everyone from the common folk to Pope Pius VII himself. He is a master of disguise and deception, frequently mingling with the lower classes in taverns and brothels, much to the dismay of his pious and conservative mother.

The film's central conceit unfolds when the Marquis discovers a perfect doppelgänger: a drunken, impoverished charcoal burner named Gasperino. Seizing the opportunity for his greatest prank yet, he orchestrates a switch, placing the bewildered commoner in his palace to impersonate him, while he gleefully takes on the role of the charcoal burner. This identity swap creates a series of chaotic and comical situations, exposing the hypocrisy and absurdity of the social hierarchy. As Gasperino navigates the alien world of nobility, and Onofrio experiences life at the bottom, the film satirizes the arbitrary nature of class, power, and justice in a society on the brink of change.

Core Meaning

At its heart, "The Marquis of Grillo" is a cynical yet comical critique of power, class structure, and the immutability of the social order. Director Mario Monicelli uses the figure of the rebellious aristocrat to expose the decadence and hypocrisy of the ruling class, which acts with impunity, secure in its divinely ordained status. The film's famous line, "Io so' io, e voi non siete un cazzo" ("I am who I am, and you are fucking nobody"), encapsulates this worldview perfectly. However, the film is not a simple revolutionary tale. It ultimately suggests a pessimistic view that nothing ever truly changes; revolutions come and go, but the powerful always find a way to remain on top. The Marquis, despite his flirtations with French revolutionary ideas, is ultimately a beneficiary of the old system and has no real desire to dismantle it. Monicelli presents a society where justice is a commodity, and personal identity is less about innate worth and more about the role one is assigned by birth.

Thematic DNA

Critique of Social Class and Aristocracy

The film relentlessly satirizes the Roman aristocracy, portraying it as decadent, detached, and absurd. The Marquis's family is a collection of caricatures obsessed with piety and lineage, while the Papal court is shown as corrupt and ineffective. The central prank of swapping identities highlights the arbitrariness of class distinctions: the poor coalman, once dressed in the Marquis's clothes, is treated as a nobleman, suggesting that power and respect are merely costumes. The Marquis's ability to act with total impunity, corrupting judges and mocking the poor, is the starkest illustration of the theme.

Identity, Duality, and Performance

The doppelgänger plot is central to the film's exploration of identity. The Marquis and Gasperino represent two sides of the same coin. Onofrio is an actor who finds his tedious noble life a role he must play, escaping it by 'performing' as a commoner. When he swaps places with Gasperino, he forces the coalman into the ultimate performance. The film questions whether identity is inherent or simply a performance dictated by social standing. Gasperino's adaptation to his new role, and the family's eventual acceptance of him, further blurs the line between the 'real' and the 'performed' self.

Power, Justice, and Rebellion

Onofrio del Grillo embodies the absolute power of the aristocracy. He openly declares that justice is not of this world and manipulates the legal system to his advantage, as seen in his dispute with the Jewish carpenter Aronne Piperno. His rebellion is personal, not political; it's a way to alleviate boredom rather than a genuine desire for social change. The film contrasts his playful insubordination with the serious revolutionary fervor of the French occupation and the grim reality of capital punishment via the guillotine, suggesting that his pranks are a luxury afforded by the very system he mocks.

Cynicism and The Immutability of Power

Despite the historical backdrop of the Napoleonic invasion and the winds of change, the film's conclusion is deeply cynical. The Pope, upon his return to power, plays a prank on the Marquis by staging a fake execution for his double, only to forgive the real Onofrio and restore him to his position. This ending reinforces the idea that the powerful protect their own and that the social order, despite seeming upheavals, ultimately snaps back into place. The phrase "when one Pope dies, another one is elected" is used to signify that the system perpetuates itself, regardless of the individuals involved.

Character Analysis

Marchese Onofrio del Grillo

Alberto Sordi

Motivation

His primary motivation is the flight from boredom (noia). Trapped in a rigid social structure and surrounded by what he perceives as fools, Onofrio uses pranks and debauchery as his escape. He is driven by a nihilistic desire to prove the absurdity of the world around him and to demonstrate his own superior intelligence and power by manipulating everyone, from his family to the Pope.

Character Arc

Onofrio del Grillo does not have a traditional character arc of growth or change. He begins and ends the film as a cynical, hedonistic nobleman who uses his intelligence and privilege for his own amusement. While his experiences impersonating a coalman and his interactions with the French offer him glimpses into other worlds and ideas (such as revolution and meritocracy), he ultimately rejects any notion of genuine change because the current system benefits him. His final restoration to his post at the Vatican signifies a return to the status quo, showing his fundamental immutability.

Gasperino

Alberto Sordi

Motivation

Initially, Gasperino has no motivation; he is an unconscious participant in the Marquis's scheme. Once he awakens in the palace, his motivation is pure survival as he tries to navigate the bizarre rules of high society. Over time, this evolves into a desire to enjoy his newfound comfort and status, leading him to confidently (and comically) inhabit the role of the Marquis.

Character Arc

Gasperino undergoes a significant, albeit temporary, transformation. Initially a simple, drunken charcoal burner, he is thrust into a world of unimaginable luxury and complexity. After the initial shock and confusion, he begins to adapt to his new role, enjoying the perks of nobility and even being preferred by some family members to the real Marquis. His journey exposes the superficiality of the aristocracy. However, his arc is ultimately tragic; he becomes a pawn who nearly pays for the Marquis's crimes with his life and is presumably returned to his poverty at the end, stripped of the status he briefly held.

Pope Pius VII

Paolo Stoppa

Motivation

The Pope is motivated by the desire to maintain the temporal and spiritual power of the Church in the face of the French invasion and internal decadence. On a personal level, he seems to have a soft spot for Onofrio, his 'favorite' but also his 'worst' nobleman, and is motivated to teach him a lesson without truly upsetting the aristocratic order that supports his rule.

Character Arc

Pope Pius VII is portrayed as a ruler who is both the head of a powerful, rigid institution and a man who possesses a certain weary indulgence towards the Marquis's antics. He represents the old world order, challenged by Napoleon. His arc culminates in him demonstrating that he is the ultimate authority, not just in spiritual matters but in the game of pranks as well. By staging a fake execution and then pardoning the Marquis, he reasserts his power in a way Onofrio can understand, effectively putting the nobleman back in his place while maintaining the hierarchical structure.

Don Bastiano

Flavio Bucci

Motivation

Don Bastiano is motivated by a revolutionary and spiritual fervor that places him in direct opposition to the established powers. He rejects the hypocrisy of the Church and the state, choosing a life of banditry. His final motivation is to face death on his own terms, delivering a damning indictment of the world and forgiving the common people, who he says "are masters of fucking nothing."

Character Arc

Don Bastiano is a brigand and a priest who represents a more genuine, albeit violent, form of rebellion than the Marquis. His character arc is short and tragic. He is a friend of Onofrio who lives outside the law and the Church's dogma. His capture and execution serve as a stark reminder of the brutal consequences of true defiance against the state. His powerful final speech from the scaffold is a moment of pure, unadulterated rebellion against all forms of authority—the Pope, Napoleon, and the executioner.

Symbols & Motifs

The Doppelgänger (The Coalman Gasperino)

Gasperino, the Marquis's perfect double, symbolizes the social construct of identity and class. He is a living representation of the idea that the only thing separating a nobleman from a pauper is circumstance, clothing, and language. His existence allows the film to physically manifest its central question about whether a person's worth is innate or assigned by society.

The Marquis discovers the drunken Gasperino in the Roman Forum and uses him for his grandest prank, switching their identities. The ensuing chaos, where Gasperino is mistaken for the Marquis by his own family, serves as the film's primary comedic and thematic engine.

The Guillotine

The guillotine, a 'gift' from the French, symbolizes the stark and brutal reality of a new, efficient, and impersonal form of justice, contrasting sharply with the arbitrary and corrupt justice of the Papal States. It represents a modernity that the Marquis finds both intriguing and threatening. It's the one consequence he cannot control with a simple prank, and it looms as the ultimate punishment for transgressing social boundaries, a fate his double nearly suffers.

The guillotine is used for the execution of the brigand Don Bastiano. Later, Gasperino, mistaken for the Marquis, is sentenced to be executed by the guillotine upon the Pope's return, bringing the film's central prank to a potentially fatal conclusion before a last-minute pardon.

Pranks (Scherzi)

The Marquis's continuous pranks are a symbol of his rebellion against the boredom and constraints of his social class. They are his only means of creative expression and asserting his individuality. However, they are also a manifestation of his power and cruelty, as they are often played on the powerless who cannot retaliate. The pranks symbolize the aristocracy's detached and contemptuous view of the lower classes, treating their lives and hardships as sources of amusement.

Throughout the film, the Marquis plays numerous pranks, from refusing to pay a Jewish carpenter and then corrupting the court against him, to tricking people with hot coins, to the ultimate prank of switching places with Gasperino. Even the Pope gets in on the act at the end, turning the tables on Onofrio.

Memorable Quotes

Mi dispiace, ma io so' io, e voi non siete un cazzo!

— Marchese Onofrio del Grillo

Context:

The Marquis says this to a group of common criminals with whom he has been mistakenly arrested in a tavern. After a police commissioner recognizes him and orders his immediate release while keeping the others imprisoned, Onofrio turns to his less fortunate companions and delivers this brutal summary of the social order before departing in his carriage.

Meaning:

This is the film's most iconic line, translating to "I'm sorry, but I am who I am, and you are fucking nobody." It perfectly encapsulates the Marquis's worldview and the core theme of aristocratic arrogance and impunity. It is a raw declaration of class superiority, asserting that his identity and birthright place him above all laws and common morality that bind ordinary people. The phrase has entered the Italian lexicon as a way to describe arrogance.

Quanno se scherza, bisogna èsse' seri!

— Marchese Onofrio del Grillo

Context:

This line is spoken as a general maxim, reflecting his approach to the elaborate schemes he concocts throughout the film. It serves as his justification for the great lengths he goes to in order to execute his pranks perfectly.

Meaning:

"When you're joking, you have to be serious!" This quote reveals the Marquis's philosophy. For him, pranks are not frivolous acts but a serious art form requiring dedication and meticulous planning. It underscores his commitment to his lifestyle of rebellion-through-mockery and highlights the paradox of his character: a man who treats the most serious aspects of life (like justice and religion) as a joke, and joking as a serious business.

Adesso, pure io posso perdonare a voi, figli miei, che non siete padroni di un cazzo!

— Don Bastiano

Context:

The revolutionary priest Don Bastiano delivers this speech from the guillotine, having refused the last rites. He addresses the crowd, condemning the powerful and absolving the weak in a final, defiant act of rebellion before being executed.

Meaning:

"And now, I can also forgive you, my children, who are masters of fucking nothing!" This is the climax of Don Bastiano's fiery speech before his execution. After forgiving the Pope ("master of heaven") and Napoleon ("master of Earth"), he turns his forgiveness to the common people. It's a moment of profound political and social commentary, suggesting that the powerless masses are absolved of responsibility because they have no agency or control over their lives, unlike the powerful who claim ownership of everything.

Il mondo è fatto a scale, Santità! C'è chi scende e c'è chi sale.

— Marchese Onofrio del Grillo

Context:

The Marquis says this to Pope Pius VII after accidentally tripping him on a small step. He turns a moment of clumsiness into a philosophical statement, cheekily reminding the head of the Catholic world about the transient nature of power, even his own.

Meaning:

"The world is made of stairs, Your Holiness! There are those who go down, and those who go up." This is a classic Italian proverb used by the Marquis to cynically explain the nature of fortune and social hierarchy. He uses it to justify his own behavior and the fluctuating fortunes of those around him. It reflects a fatalistic but opportunistic view of the world, where social mobility is a game of chance and power shifts are inevitable.

Philosophical Questions

Is identity inherent or a social construct?

The film explores this question through the central plot device of the doppelgänger. When the coalman Gasperino is dressed in the Marquis's clothes, he is accepted as the Marquis, despite his radically different behavior. This suggests that identity, at least in the eyes of society, is overwhelmingly determined by external markers like wealth, title, and attire. The ease with which the two men swap roles implies that the 'self' is not a fixed essence but a performance shaped by societal expectations and class structures.

What is the nature of justice in a hierarchical society?

"The Marquis of Grillo" presents a deeply cynical view of justice. The Marquis explicitly states that justice is not of this world and demonstrates this by bribing judges and clergy to win a lawsuit against a poor Jewish carpenter. Justice is depicted not as a moral principle but as a tool of the powerful, used to maintain their status and oppress the weak. The film asks whether true justice can ever exist in a system where individuals are not equal before the law, a question epitomized by the line "I am who I am, and you are fucking nobody."

Can rebellion exist within a system without seeking to change it?

The Marquis is a rebel, but only on his own terms. He defies social norms, mocks the Pope, and flouts his duties. However, his rebellion is purely for personal amusement and never challenges the fundamental structure of the society that grants him his privilege. He is intrigued by the revolutionary ideas of the French but ultimately sides with the system that benefits him. The film forces the viewer to consider the difference between genuine revolutionary action (like Don Bastiano's) and the self-serving, aesthetic rebellion of a privileged individual who wants to break the rules without consequence.

Alternative Interpretations

While the dominant interpretation sees the film as a cynical critique of an immutable class system, some alternative readings exist. One perspective might view the Marquis not just as a cynical antihero but as a figure of existential rebellion. Trapped in a meaningless world of ritual and tradition, his pranks can be seen as an attempt to assert his freedom and create his own meaning, however nihilistic. His actions, though cruel, consistently expose the absurdity and hypocrisy of the institutions around him, making him a kind of chaotic agent of truth.

Another interpretation could focus on the ending with more optimism. The final prank played by the Pope on the Marquis could be read as a subtle lesson in humility. The Pope, the ultimate authority, demonstrates that even the Marquis is just a player in a larger game. By forgiving him, the Pope shows a form of grace, suggesting that the system, while flawed, has the capacity for mercy and can absorb and neutralize rebellion without resorting to pure tyranny. In this reading, the restoration of the status quo is not just cynical, but a demonstration of the system's complex resilience and its ability to tolerate (and even be amused by) its own internal critics.

Cultural Impact

"The Marquis of Grillo" is considered a masterpiece of the "Commedia all'italiana" (Comedy Italian-style) genre and one of Mario Monicelli's most celebrated films. Released in 1981, it arrived at a time when the genre's golden age was waning, yet it achieved enormous popular and critical success, proving the continued viability of historical satire. The film's enduring popularity in Italy is immense; its lines have become proverbial, and it is frequently broadcast on television, beloved by generations of viewers.

Alberto Sordi's portrayal of Onofrio del Grillo is iconic, perfectly capturing a cynical, irreverent, but ultimately charming Roman aristocrat. The character has become a symbol of a certain type of power that blends arrogance with wit. The phrase "Io so' io, e voi non siete un cazzo" has transcended the film to become a part of the Italian cultural lexicon, used to humorously or critically describe blatant assertions of privilege and power.

The film's influence lies in its masterful blend of comedy, historical drama, and sharp social commentary. It critiques the power structures of Papal Rome but with a universally resonant cynicism about class and justice that keeps it relevant. While not directly spawning sequels or remakes, its spirit can be seen in later historical comedies that use the past to comment on the present. It remains a high-water mark for Italian historical comedy, praised for its lavish production design, witty script, and a legendary central performance.

Audience Reception

Audience reception for "The Marquis of Grillo" has been overwhelmingly positive, particularly in Italy, where it is considered a beloved classic. Viewers consistently praise Alberto Sordi's masterful and charismatic dual performance, which is often cited as one of the best of his career. The film is celebrated for its sharp, witty dialogue and its memorable, often-quoted lines, especially the famous "Io so' io, e voi non siete un cazzo!". The humor, which blends slapstick, satire, and dark cynicism, is another highly praised aspect.

The lavish and detailed historical reconstruction of early 19th-century Rome, including the costumes and sets, is widely admired and seen as a key element of the film's appeal. The main points of criticism, though rare, sometimes point to the film's long runtime (over two hours) and a narrative that can feel episodic rather than tightly plotted. Some modern viewers might also find the Marquis's cruelty and the film's cynical conclusion unsettling. However, the overall verdict from audiences is that it is a timeless masterpiece of Italian comedy, brilliantly satirizing power and society with intelligence and humor.

Interesting Facts

- The character of the Marquis is loosely based on a real historical figure, Onofrio del Grillo, who lived in the 18th century (1714-1787), not the early 19th century as depicted in the film. The film moves his life forward to place it during the Napoleonic era.

- The film's most famous line, "Io so' io, e voi non siete un cazzo!", was not invented for the movie but was appropriated from the 1831 sonnet "Li soprani der monno vecchio" ("The Rulers of the Old World") by the great Roman poet Giuseppe Gioachino Belli.

- The film won the Silver Bear for Best Director for Mario Monicelli at the 32nd Berlin International Film Festival in 1982.

- Many scenes were filmed in real historical locations in Rome, but the Marquis's residence is depicted as the Casa dei Cavalieri di Rodi in the Forum of Augustus. Other locations include Palazzo Pfanner in Lucca and the Capitoline Museums in Rome, which stood in for the papal apartments at the Quirinal Palace.

- The opera featured in the film, "La cintura di Venere" by Jacques Berain, is entirely fictional. Composer Nicola Piovani created the music and has expressed amusement that scholars have sometimes tried to find information on the non-existent opera and its composer.

- Historical inaccuracies are present for narrative effect. The French occupation of Rome shown in the film (1809) actually began in 1808, and the news of Napoleon's defeat in Russia arrived in 1812, not within the film's compressed timeline.

- The role of the Marquis was a defining one for Alberto Sordi, cementing his status as one of the greatest interpreters of "romanità" (the essence of being Roman) in Italian cinema.

⚠️ Spoiler Analysis

Click to reveal detailed analysis with spoilers

Frequently Asked Questions

Explore More About This Movie

Dive deeper into specific aspects of the movie with our detailed analysis pages

Comments (0)

No comments yet. Be the first to share your thoughts!